I had in mind to talk about two unrelated aspects of this odd journey, but I realized that they both actually converge under the general category of “holes”. Some folks like reading about the gory details of life, some want stratospheric reflections. Well, here you get both.

At some point in this new treatment regimen, I’m going to have a port put into my chest. It’ll likely be a sort of central venous catheter. Honestly, though, I’m not really thinking about that right now.

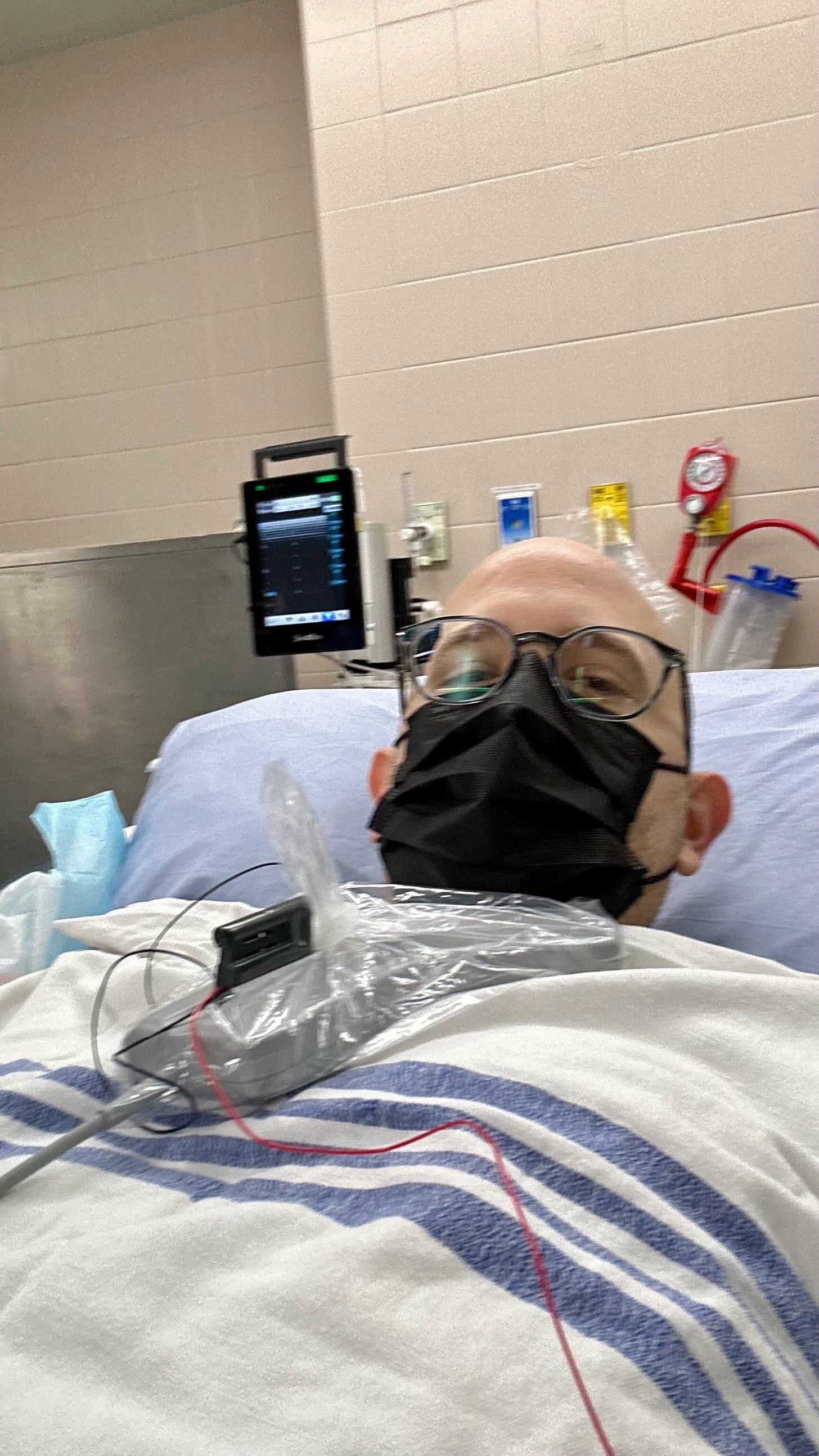

During the process of moving from pancreatitis to cancer, I had both a biliary drain installed on my right side, basically at the bottom of my ribcage, and then later a PICC line to administer chemo, serve as a blood draw, etc.

I barely want to talk about what it was like to have the biliary drain. It’s not so much that it’s gross, or humiliating, or anything like that—more so that it was just an utter handcuff for the entire time it was in place. For all its annoyances, it did do something: it allowed me to recover from jaundice, which is a waking nightmare in its own right. But it severely restricted my movement, occasionally leaked, and having the dressing changed was…unpleasant. I couldn’t look at it when the home care nurse performed this kindness every week. And, on some unfortunate occasions, when my partner had to do so in an emergency leakage situation.

It was nothing more than a small tube with a valve. But it was coming out of me, from inside me, where it was doing something. And that is weird.

The PICC line roamed within the same uncanny valley. A tube coming out of my right bicep with two little ports (lumens) used for both introducing and escorting away liquids to and from my veins. The ease of drawing blood (most of the time) was a convenience I’ll not soon forget each time I’m stabbed now that it’s gone. The ease of pumping chemo into my body was also a strange convenience.

But still: my body knew it bridged a world where lines shouldn’t be crossed. I initially ended up as an inpatient because of a blood clot that saw my arm swell up like Popeye’s. My son knew something was not quite right whenever he went from playing with the computer’s power cable to seeing that, oh, interesting, dad has a power cable too!

Thankfully my son would get distracted each time he saw my owl tattoo. “Hoot” might’ve been one of his earlier words, come to think of it. He has a number of owl toys. He also has a book—one of our favourites—Little Owl Lost, where the refrain is “uh oh!” Hearing him say “uh oh!” in his tiny voice still melts me. It doesn’t matter if he’s dropped his spoon during breakfast or is pointing at the page where the baby owl falls out of the nest. Every. Single. Time. Melt.

But there have been many days and weeks over the past month where I have only heard these vocalizations from behind a closed bedroom door. Not to be the bearer of a sad segue, but this is one of the things you just have to deal with as a parent whose body is being contorted in a way that leaves you unable to do much to physically bond with your (now) toddler. Because of the drain and the PICC, I wasn’t able to lift him or carry him for months, much less sit with him at mealtimes, push him in a stroller, save him from falling off the play structure.

I’m grateful that my partner makes every effort on “bed days” to have story time at night by my side when I’m up for it. Any time I have the energy to be around him, I’ll take that opportunity. But there have been many, many days between diagnosis and now when he’s asked “Dada?” and mom has to say something that will appease a very small human’s desire to hang out with his dad.

I’m not saying any of this to generate oozing sympathy or appeal to something emotionally gross and manipulative. I’m just trying to express something I realized that ended up being surprising to me.

I’m an Old Dad. (If you have a kid younger than two and you’re forty, you’re an Old Dad.) I didn’t think I would ever be a dad—for a very long time—so really, being an Old Dad was my only option. And while I love my son more than you can possibly imagine, being an Old Dad means that I also love my son’s nap times more than you can possibly imagine. I love him, but he is exhausting. He’s a toddler.

I was surprised to learn that the times when I have had zero responsibilities to mind my child were not considered by my Old Dad brain to be “rest”. Don’t get me wrong, you need vacations from your kids. You need an opportunity for your nervous system to reset. But this is not the context for that. Instead, the lizard-brain subsection of my consciousness has often gone straight to guilt, at best, and despair, at worst. But not rest.

I need breaks from my kid. But I desperately don’t want a break from my kid, if that makes sense.

I think it’s important to underscore that I don’t doubt the resiliency of my son through all of his experience of the past almost-year. Despite his inability to truly understand what’s happening to me, once I’m able to reestablish an emotional connection with him (whether that’s returning from a hospital stay or emerging from my cocoon) he seems right as rain. I do sometimes doubt my resiliency, however. He might not remember any of this. But I will always remember this. There will always be holes in the retelling of this part of his life.

Once again, there’s no “solution” here. I think it just bears repeating out loud that these are strange circumstances, that we’re all doing our best, and that the holes left in my memory regarding this period of my son’s life are actually neutral artefacts. It doesn’t mean I’m not sad or frustrated or even angry for moments of absence, or overjoyed and ecstatic for moments of presence. It’s just that I don’t think you can’t make up for lost time; you do the best you can with what you have.

I would be just fine not having any more holes poked into my bag o’ bones. But I can’t guard as well against the emotional holes.